Poor Things and the Folly of Patriarchal Feminism

As the reviews for Poor Things, Yorgos Lanthimos’ latest film starring Emma Stone, Willem Dafoe, Mark Ruffalo and Ramy Youssef, started coming in, I was ready to dislike the film based on those alone. I’ve seen the trailers, of course, and was cautiously optimistic, despite the magnification and stylization of the “Born Yesterday” trope: a particularly unsettling film cliché that makes painfully obvious the fascination of older men with young, almost childlike, women. In addition to that, most of the reviews (written by men) praised the film for its inventiveness, bold use of sex scenes, unabashed wide-eyed joy and freedom, and a pure lust for life, mostly provided by Emma Stone as Bella Baxter. The reviews went on to say that the Poor Things tracked the protagonist’s fascinating development from a naïve child to an erudite woman, a feminist retelling of Frankenstein – indelible, inventive, incredible!

… or I Shouldn’t Have Read the Book

As the reviews for Poor Things, Yorgos Lanthimos’ latest film starring Emma Stone, Willem Dafoe, Mark Ruffalo and Ramy Youssef, started coming in, I was ready to dislike the film based on those alone. I’ve seen the trailers, of course, and was cautiously optimistic, despite the magnification and stylization of the “Born Yesterday” trope: a particularly unsettling film cliché that makes painfully obvious the fascination of older men with young, almost childlike, women. In addition to that, most of the reviews (written by men) praised the film for its inventiveness, bold use of sex scenes, unabashed wide-eyed joy and freedom, and a pure lust for life, mostly provided by Emma Stone as Bella Baxter. The reviews went on to say that the Poor Things tracked the protagonist’s fascinating development from a naïve child to an erudite woman, a feminist retelling of Frankenstein – indelible, inventive, incredible!

Now, I’ve become a shrewd hag in recent years, wandering the woods sniffing out innocent victims to lecture them on feminism – this is my lot in life and I will bear it. In addition to my full-time hobby of being as annoying as possible, I also developed somewhat of a sixth sense when it comes to supposedly feminist movies, or rather the vocabulary used by film critics to describe them. “Bold, inventive, playful, joyful, creative” – these words come to mind when I recall this particular kind of criticism directed at Greta Gerwig’s latest juggernaut, Barbie (which I liked, chill!).

In my review of Barbie, however, I concluded that its specific brand of feminism was rather exclusionary in nature, pertaining to only a handful of privileged, mostly white, able, and wealthy women, whose experiences with the patriarchy are, while still quite uncomfortable and painful, mitigated by their position in our flawed society. Within this framework, however, the film does genuinely try to convey a “girl power” message and, supported by great acting, directing, and writing as well as an extraordinary production design, somewhat succeeds.

Why am I talking about Barbie?

Well, in both films we follow a very sheltered female protagonist with no clue about the social norms of the outside world as they’re plunged into a patriarchal society. They emerge from it (kind of) unscathed only due to their cheery and innocent outlook in life. It is their innocence and inquisitiveness about the origins of the oppressive norms they encounter, and their subsequent understanding that most of them are nonsensical, that leads the now enlightened women to the desire to better humanity and/or themselves.

I’ve written extensively on why Barbie simultaneously fails and succeeds in regard to its plot, but compared to Poor Things, it is indeed a feminist masterpiece.

🚨MASSIVE SPOILERS AHEAD!🚨

1. The Curious Case of Alisdair Gray

Alisdair Gray was a staunch postmodernist, imbuing his sometimes outrageous tales with, as is genre convention, a flurry of literary references, narrative traps, some well-placed low-brow humor and, in his case, fervent anti-authoritarianism. Poor Things, published in 1992, ticks all of the above and more. In addition to the prose, the story is told through illustrations, author’s notes and even a fake erratum. By the end of the book (yes, including the erratum) the characters feel so painfully real that saying goodbye to them was inexplicably woeful.

But first: a short summary.

In 1990 Alisdair Gray gets his hands on a book entitled EPISODES FROM THE EARLY LIFE of a SCOTTISH PUBLIC HEALTH OFFICER/Archibald McCandless M.D., which his friend and historian Michael Donnelly rescued from the municipal incinerator in the 70-ies. He finds the book so fascinating that he agrees to act as editor and publish it with some minor changes, like the title, which he changes to Poor Things. What follows is his account of checking historical facts and confirming, at least for himself, that everything in this book is historically accurate.

In McCandless’ account of his early life, we learn about his upbringing in rural Scotland, his outcast status at Glasgow University where he’s studying medicine, and his friendship with Dr. Godwin Baxter, a genius surgeon and researcher at the university. His friendship with Baxter, whom he describes as being of hideous appearance, but of a mild and friendly demeanor, develops over the course of long walks, both outsiders having found themselves enjoying each other’s company. Before long, Baxter invites McCandless to his house, where the young man meets Ms. Dinwiddie, Baxter’s trusted housekeeper, as well as Bella Baxter, Godwin’s supposed niece.

McCandless is immediately smitten with beautiful Bella and her peculiar childlike behavior. As he inquires further about her, Baxter reveals that, by means of no importance, he had procured the fresh corpse of a pregnant woman, who had drowned herself, and then revived her with science. He proudly continues to expand on his medical escapades, until he excitedly admits the full truth of his experiment: respecting the woman’s wishes to remain dead, he, instead of reviving her brain, transplanted her infant’s brain into her head, thus making Bella Baxter. McCandless is both fascinated and appalled, both at Baxter playing God and succeeding and at his ulterior motives regarding Bella.

Baxter plans to educate Bella into a fine young woman (again) and then marry her, for he is “about to possess what men have hopelessly yearned for throughout ages: the soul of an innocent, trusting, depending child inside the opulent body of a radiantly lovely woman” (pp. 35-36). Huffing and puffing, McCandless swears to protect her honor. To be fair, at this stage of the story he only half believes that Bella was revived by Baxter, instead choosing to believe Baxter’s cover story of her having been in a horrific train accident, which left her severely mentally disabled1.

Apart from teaching Bella everything he knows about medicine and other sciences, Baxter plans an around-the-world tour with her, where she continues to be educated by several different teachers. Therefore, McCandless next meets Bella and Godwin fifteen months later, while walking in the park. Bella seems much older and now displays the intellectual capabilities of a very precocious ten-year-old. Anyway, they get engaged in the bushes (for marriage). Before they can enter into marital bliss, however, Bella is seduced by skeezy Duncan Wedderburn and, having discovered her adventurous spirit and interest in sex (she mentions “kissing hands” with one of her female teachers), lets him whisk her away, fully intent on using him for sex and further education away from her parental figure, whom she calls God (cute).

Having been deprived of his child bride, McCandless is understandably listless, but Baxter assures him calmly that this is an educational matter and Bella will soon tire of Wedderburn and return to Glasgow to marry him. After a while, they get two letters from Duncan and Bella, respectively. Both describe their elopement across Europe, through the Mediterranean, to Odessa and finally Paris.

Wedderburn describes a horrific odyssey, in which he’s used and abused by Bella, while having only the best intentions of making her his wife and the lawful Mrs. Wedderburn.

“I exposed all my past iniquities more frankly and fully than I ever have courage and space to do here […] because (blind fool that I was) I believed we would soon be man and wife! […] I was so sure Bella would soon be my bride that, by a piece of harmless chicanery, I obtained a passport on which we were named as husband and wife.” (p. 81)

She, however, refuses to marry him and continues to spend his money and ply him with sex and alcohol, whether he wants it or not. Finally, Wedderburn finds God and determines that Bella must be the bride of Satan, a Jezebel, the whore of Babylon, and Godwin the Devil who unleashed her upon the world. As Bella practically abandons him to his fate on a train back to Glasgow, he is then admitted to an asylum by his mother upon arrival.

Bella’s letter tells a different story, and we finally get an unadulterated look at the world from her perspective, half-way through the book, which is still interspersed with occasional commentary from McCandless and Baxter.

Her story details their journey through Europe, where they partake in hours of “wedding” (this is how Bella calls sex). Wedderburn is uptight and possessive from the start and often questions Bella about her whereabouts and with whom she’s spoken.

“I’m not the only man you ever loved – admit it you have had hundreds before me!”

“Not hundreds – no. I never counted them, but half a hundred might be about right.”

He gasped, gaped, groaned, writhed, sobbed and tore his hair then asked for details.

That is how I learned that he did not think that kissing hands is love.

Love (Wedder thinks) only deserves the name when men insert their middle footless leg.

“If that is so Dear Wedder, rest assured you are the only man I ever loved.”

“ Liar cheat whore!”, he screamed. “I am no fool! You are not a virgin! Who deflowered you first?” (p. 106)

They travel some more, which Bella finds boring and is constantly put upon by Wedderburn’s jealousy. She describes being in a waking sleep most of the time, until she jolts awake in a gambling den in Odessa. For a while, Bella puts up with Wedderburn winning and losing and whining and bitching, but doesn’t take him very seriously. As Wedderburn’s obsession starts to take over their entire life, however, with him spending everything on his drug and gambling addiction, Bella feels increasingly sorry for him and takes on the responsibility to somehow get him back to Glasgow and subsequently get rid of him.

To that end she persuades Duncan to board a simple cargo ship from Odessa to Marseille, where, she hopes, he’ll be able to kick his addictions. On the ship, Duncan is increasingly unresponsive and takes up the Bible, while Bella consorts with the other passengers. She befriends Englishman Harry Astley, a nihilist, and Dr. Hooker, an American racist. One day, after much discussion of the white man’s burden, the good doctor volunteers to show her the “real world” by taking her on an excursion when they make halt in Alexandria.

There, they stop at a posh restaurant, which is exclusively frequented by whites. In front of the restaurant, however, Bella sees The Poor (tm) “amusing folk on the veranda by bowing and praying to them and wriggling their bodies and grinning comically until someone on the veranda flung a coin” (p. 172). Bella runs out, as she sees a young blind girl carrying a baby, to give her money. Her purse tears, and she is swamped by sick and writhing children trying to get to the coins, while she tries to save the girl and her baby and bring them home with her. Astley and the doctor talk her out of it, and the crowd is violently dispersed.

After being dragged away kicking and screaming, Bella returns to the ship distraught and in a haze, only to find a deeply depressed unresponsive Wedderburn. She then proceeds to repeatedly have sex with him against his wishes, which she acknowledges and still continues, leaving him a broken man.

"The damage to Wedder was done after I returned from Alexandria. I rushed into our cabin and wed wed wed wed him, wedding and wedding and wedding until he begged me not to, said he could give no more but he could and did – it was the only thing which stopped me thinking about what I have seen.” (p. 153)

From further conversations with Hooker and Astley, with whom she begins a short-lived platonic romance, and her readings on different ideologies, in the days that follow Bella concludes that she must become a socialist and fight for a better society. She also writes that this is where she finally shed her childhood selfishness.

They arrive in Paris and, after Wedderburn gambles away their last money while she is procuring lodgings for them, Bella finally breaks into her secret stash Baxter gave her at her departure and sends Duncan back to Glasgow. Now penniless herself, she goes to work as a sex worker to do “a job as well and fast as possible, not for pleasure but cash like most people do” (p. 180). She chooses to leave the establishment a couple of weeks later, because she doesn’t agree with the administrative health officials’ harassment of the sex workers under the guise of a health inspection.

She then makes it to Glasgow anyway.

As soon as Baxter and McCandless stop reading her letter, Bella arrives and is now ready to marry the latter. Their wedding is however interrupted by two men claiming to be Bella’s, or Victoria’s as they call her, husband and father respectively. What follows is a long-winded back and forth, where both sides try to prove that Bella is and is not Victoria2. After Bella refuses to leave, her alleged husband Colonel Aubrey la Pole Blessington tries to kidnap her by force but is stopped by Bella herself. She then recognizes him as a client from her days at the brothel and he silently kills himself a couple of days later, which frees Bella/Victoria up to finally marry McCandless.

They marry, Godwin dies and bequeaths them all his money, Bella decides that she has to become a doctor to heal the world and becomes a famous practitioner with her own charity clinic as well as a prominent member of the Fabian Society3. Everyone lives happily ever after.

The End.

Gray is the first narrator we encounter in the book, followed by McCandless himself, Duncan Wedderburn, Bella Baxter and finally Victoria McCandless M.D. – all of which are extraordinarily human and delightfully unreliable. Their tales, when pieced together, however, tell a fascinating story about Victorian society, the full scope of its (ridiculous) political, medical, and societal mores, and how these notions still affect our modern sensibilities, our imagination and British society overall.

Sprinkle in a ton of references to Victorian gothic literature (Frankenstein, H.G. Wells), some modernist classics (Lolita) and a smattering of Russian literature, combine with full-grown men cringing at the mere mention of lady parts and what to do with them, seal the deal with the stark realism, and you got yourself a postmodernist nightmare masterpiece.

The book is unapologetically political, invoking colonialism and all its horrifying consequences as well as early forms of socialism and feminism, including the suffragette movement. At its core, it asks and fails to answer the age-old question – what makes us human? – making itself part of the huge tapestry of the Nature vs. Nurture debate. In the end, Gray settles on the notion that a fully adult person is only a politically educated one – a person who can, with conviction, take on the responsibility for themselves as well as for others. It is not a feminist book, but it is a book about feminism and how a woman of any century develops an ideological sense of right and wrong.

The reason as to why the whole “child bride” thing doesn’t feel as uncomfortable in the book, as it will in the movie, is because it has a clear narrative purpose. Bella’s childishness is not supposed to be taken literally. It’s representative of the selfishness and short-sightedness of a politically uneducated person. When Bella witnesses the horrors of poverty and her own role in creating it in Alexandria, she decides to become a political actor and consequently sheds her childlike demeanor and becomes an adult.

Bella develops a sense of responsibility and compassion even for a toxic worm like Wedderburn and then curates and nurtures it into a fully formed conviction. Only when Bella fully understands the cultural, ideological, and philosophical background of the words and convictions hurled at her from every man she encounters, is she able to find herself in the midst of all their grandstanding – and defy them.

The film, however, made some changes…

2. No Thoughts, Just Vibes

In the epilogue to Archie McCandless’ book, Alisdair Gray includes a letter from Dr. Victoria McCandless M.D., in which she speaks up against the supposed autobiography her late husband wrote about her. She tells her own story, which is much more compelling, albeit not as fantastical as Archie’s Frankenstein pastiche. After relaying her version of events, while she tries to surmise why he would write something like that about her, she says this:

“Having had a childhood, which privileged people would’ve thought “no childhood”, he wrote a book suggesting that God had none either – that God had always been as Archie knew him, because Sir Colin [Baxter’s father] had manufactured God by the Frankenstein method. Then he deprived me of childhood and schooling by suggesting I was not mentally me, when I first met him, but my baby daughter. Having invented this equality of deprivation for all of us, he could then easily describe, how I loved him at first sight and how Godwin envied him.” (p. 273)

Victoria exposes McCandless’ memoir as a lie, a book he wrote while already bedridden due to MS, and the last hurrah of a loving, but jealous husband. And regardless of whether that’s true or not, as, in my opinion, both of their accounts are bound to teem with truths and untruths alike, we still get a fuller picture of those people, of their imperfections and ridiculous humanness and all that they wanted to bring to light and keep hidden.

Here's what Tony McNamara, the writer of Poor Things (2023), has to say in this regard:

““The fingerprints of childhood and society weren’t on her as a character,” McNamara tells Variety’s Awards Circuit podcast. “I’m writing someone who just greets experience in a really open, adventurous, optimistic [way]: ‘I wonder what it is. And I don’t have any preconceptions about how I should feel about it, how I should judge it. Anything. I’m just in a constant state of self-creation.’“ (Riley 2024)

It is no surprise then that the movie only adapts McCandless’ version of events.

The skeletal structure of the plot is mostly intact: Godwin (God) Baxter (Willem Dafoe) makes Bella (Emma Stone), Max McCandles (Ramy Youssef) finds out about it and falls in love with her, they get engaged, she runs away with Wedderburn (Mark Ruffalo), sees horrible things in Alexandria, works at a brothel, comes back and gets ambushed by her ex-husband Alfie Blessington (Christopher Abbott), marries McCandles and lives happily ever after, while studying to be a doctor.

The similarities end here, however. Lanthimos and McNamara neither bothered to take the epilogue into account, nor were they particularly interested in the politics of the very political book they were adapting. They blunder into every poorly concealed plot trap Alisdair Gray had laid, as some of the changes in the movie convey the exact opposite message compared to the book, and also skew into a kind of childish cruel humor, which is never shown to have any narrative purpose.

Just like in McCandless’ memoir, Godwin Baxter is portrayed as an actual Frankenstein’s monster of his father’s design, who abused and mistreated him by relentlessly experimenting on his body, until he required special assistance to live. This abuse, however, is never reckoned with in the film. Baxter’s physical insufficiencies are frequently used as comic relief, and his tendencies to use and abuse humans for science which directly resulted from his father’s abuse are depicted as unpleasant, but harmless. Godwin’s designs on Bella as a sexual partner are erased completely, due to the decision to make him a eunuch in the film, therefore also stripping him of any human desire.

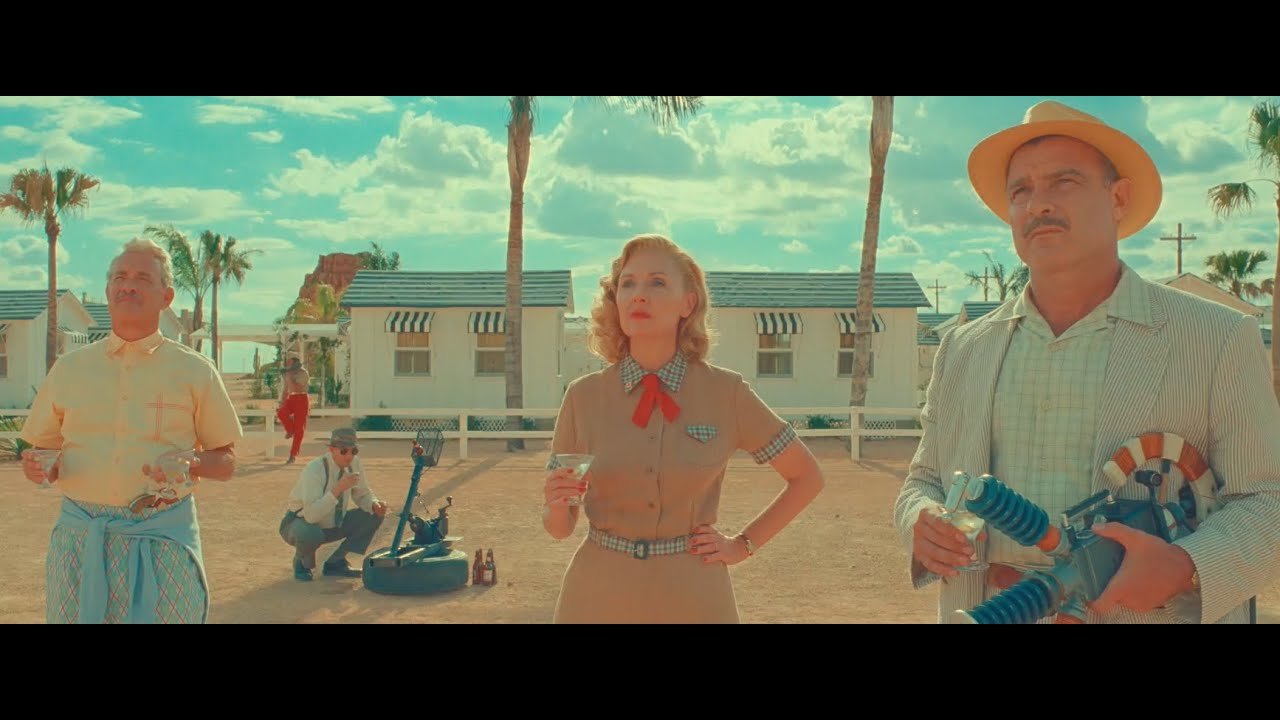

Seen here: Fun!

This metamorphosis from a character with both complex and very real motivations into a flat caricature befalls all of the side characters that made it from the book into the movie, as well as most of the newly invented characters.

Max is a bland yes-man and complacent to a point where I had to wonder, whether both Lanthimos and McNamara view men who express any kind of agreement with feminist ideas as weak and effeminate. Blessington is a gun-wielding one-note villain, Wedderburn is a cardboard cutout toxic boyfriend, Harry Astley (Jarrod Carmichael) is a guy that exists, and don’t get me started on all the other female characters except Bella.

3. Sex, Sex, Sex!

Sex is quite important to Bella in the book. Her descriptions of her “wedding” Wedderburn or her clients are not graphic, but rather show a secure contentment in her needing this kind of pleasure. This normalizes female sexuality, rather than exotifying it. In his, I admit, quite clumsy way Gray reassures readers that female sexuality is normal, that it’s neither superior nor inferior to male sexuality.

In the movie Bella calls sex “furious jumping”, and it looks like bargain bin porn.

Bella’s sexual awakening begins with a disastrous excursion into the outside world. You see, additionally to him being a source of comic relief, Godwin is also portrayed like the father in a 1980-ies sitcom. He’s overly possessive and protective of Bella, to a point where he doesn’t let her out of the house. On one occasion, Bella persuades Baxter and McCandles to let her go outside. As you might’ve guessed, Bella doesn’t get any educational travel in the movie. Their little foray ends in disaster, as Bella throws a temper tantrum, because God doesn’t let her out of the carriage to get ice cream. Reasoning with a toddler is hard, so Baxter and McCandles do the only humane thing: they violently sedate Bella with chloroform and carry her unconscious body back to the house4.

There, while still unconscious, she’s stripped naked by the housekeeper Ms. Prim (Vicky Pepperdine) in a long, porn-like scene, where we the voyeuristic audience get a full-frontal view of her smooth hairless body. Here begins the film’s obsession with sex and Bella’s genitalia, for all of Bella’s growth as a person as well as a political entity is closely tied to her sexual desires and nothing else.

For this to work, however, Lanthimos has to establish a new baseline for desired sexual behavior:

Immediately after the above scene, Bella awakens from her chloroform-induced slumber and starts masturbating. Not only is she instantly good at it, she also has a lot of fun doing it. So much so that she tries to masturbate at the breakfast table, proudly wanting to show Ms. Prim that she’s found a way to always be happy. Comically appalled, Ms. Prim, who hates Bella for no reason other than comic relief, leaves the room in a huff. Max, who was hired by Baxter to track Bella’s development and has hopelessly fallen in love with her by now, walks in and hurriedly stops her by explaining that that’s not proper behavior. Like the toddler that she is, Bella doesn’t like to be told off for something that she likes doing, but unlike a toddler, she doesn’t ask any questions as to why she’s not allowed to do it, she just accepts and rebels against it.

Lanthimos chooses this contrived “not allowing someone to masturbate at the breakfast table” norm as the basis of an entire narrative around Bella rejecting all oppressive societal norms, ultimately revealing the core principle of the movie – the notion of a personal freedom born out of the lack of life experience and, therefore, shame. This has been confirmed in several interviews.

Here’s Lanthimos in The Guardian:

“Well, shame is one thing that we are conditioned to feel in certain situations and Emma’s character doesn’t have that,” he says. “She never got to know what shame is, so she is totally free to give her mind, her thoughts, her opinions, her body, whatever.” (Kermode 2023)

And here’s McNamara again:

““There is a kind of wish fulfillment in the movie,” he adds. “Like, What would my experience be if I could let go of all this stuff I carry around?”“ (Riley 2024)

The result is horrifying. Ridding Bella of story, experience and depth means that she also doesn’t develop any boundaries, physical or mental. With Bella’s lack of understanding of healthy boundaries and with her inquisitive nature severely diminished, it’s not a surprise that her tryst with Wedderburn looks much different in the movie.

In the book Wedderburn is established as a skeezy lawyer, who one day visits Godwin to set up his will. When he spots Bella, he immediately wants and seduces her, which starts their little sexcapade. The movie, however, has to go out of its way with his introduction. It starts out similarly. Wedderburn visits Godwin to set up his will, he spots that Baxter wants to bequeath all of his money to Bella and comments on how extraordinary a woman must be to elicit such trust.

Mothers, lock up your daughters!

He excuses himself to go to the bathroom, but immediately starts creeping through the mansion like a cartoon villain, peeking into all the rooms in search for Bella. While sulking in her room, because she can’t masturbate at the table, she’s found by Wedderburn. After they exchange a couple of words, he immediately molests her by nonchalantly putting his hand between her legs. As Bella doesn’t have any boundaries, she just accepts it and wants more, because it felt good5.

By skewing our perspective on the idea of what a healthy sexual relationship actually looks like, the movie supplants it with its own version: a version where no one cares much for consequences or informed consent, and where the entirety of female bodily autonomy is purely expressed by Bella craving, getting, and enjoying lots of straight penetrative sex6.

A baseline where boundaries and consent are anathema to joy.

Later in the brothel, Bella does express some concerns about consent and the degrading practice of letting a man choose a prostitute from a line-up. However, she does so, because the man in question, played by French actor Laurant Borel, repulses her so much, she’s ready to start a revolution over it. This scene ends with Toinette (Suzy Bemba), a fellow prostitute, then having to service him for free with no consequence to Bella’s philosophy or development.

Toinette pondering her life choices.

It’s hard to ignore how this newly established baseline for female sexuality showcases the “correct” way of how women are supposed to react to sexual advances, and even how they’re supposed to enjoy sex in general. Moreover, it establishes that there are no unwanted sexual advances, and that penetrative sex is the pinnacle of pleasure7. Bella’s supposed freedom and wide-eyed joy is primarily devised for straight men – their gaze, their tastes, their fantasies.

Lanthimos and McNamara engineered themselves the perfect waifu!

Fathers, lock up your sons!

In one of the more iconic scenes of the movie, Bella hears music and instinctively gives in to it and starts dancing furiously. In this flurry of silk gown and limbs, we’re supposed to see a freed woman - free of shame, self-consciousness and oppressing societal norms. And while I also desperately want to give in, surrender to the film’s absurdity, I’m instead horrified by the director openly grooming the audience; pulling us into his fantasies of the perfect, naïve, boundary-less woman, who never says no, indeed never even thinks about this word.

4. Am I the Drama?

Bella and Wedderburn dance for a while, until he assaults a man for flirting with her. He then, turned on by Bella’s free-style dancing, proceeds to ask her to marry him, which she refuses. Instead, she tells him rather impartially about a sexual encounter with another man, which Wedderburn takes… badly. So badly that next day, he lures her into a huge trunk and kidnaps her onto a ship bound to France8.

On the ship, Bella is distraught at first, furious at Wedderburn for kidnapping her. However, although she makes fast friends with fellow passengers Harry Astley and Martha Van Kurtzroc9 (Hanna Schygulla), she doesn’t tell them about the kidnapping, not even in passing.

Remember kids, real feminists don’t ask for help, even when they’re being kidnapped!

While Wedderburn continues to be a colossal dick, Bella spends her time with Astley, whose characterization is best summed up with “some guy”, and Martha, who gives Bella books on various subjects and is genuinely nice to her. For the crime of making Bella marginally smarter, however, Wedderburn attempts to murder Martha, which is played as a gag, and no one is mad at him for it.

One day Astley decides to shake Bella from her naivete and show her “the real world” at their next stop in Alexandria.

…

Let’s talk production design.

Poor Things is, for all intents and purposes, a beautiful movie. From its distinct acting style to the writing and costume design it’s supposed to evoke a grand adventure, a human experience without the baggage of social mores.

The production design, free from the limits of “boring adult” imagination, shows the world through the eyes of a child … a retro-futuristic, Belle Epoque-inspired child. Designers James Price and Shona Heath employ miniatures and beautifully painted backdrops to evoke a theater production with a grand budget, whose cardboard fakeness and creamy pastel color palette give the movie a magical DIY feel. Price and Heath perfectly encapsulate the grand childhood adventures I had just by sitting in my room with some cardboard cut-outs and a very active imagination (minus the sex-stuff).

However, the drawback to the whimsy is that Bella’s character-defining moment in Alexandria falls incredibly flat. In the movie, Alexandria is an island akin to an elaborate amusement park attraction, consisting of a restaurant situated on a high cliff, said cliff and something indistinguishable at the bottom of the island. When Harry and Bella look down the sheer cliff into the indistinguishable abyss, they just see some nondescript brown people writhing and moaning in a … Poor Pittm. This distance completely takes away the visceral component of Bella’s experiences in the book. So, when she tries to hurl herself off the cliff and collapses crying, it is nothing more than a childish overreaction.

A reaction, which, according to the movie, she has to grow out of. So, she runs back to the ship, gathers all of Wedderburn’s money and runs out again in an attempt to … throw it into the Poor Pit (tm). Unfortunately, she’s intercepted by two sailors, who say that she can’t go anywhere, as the ship is about to cast off. Instead, they offer to safeguard the money for her and give it to The Poor™ on her behalf, while cartoonishly grinning at each-other.

With that the movie flattens and cheapens Bella’s desire for a better world. Don’t even try, it says, derisively. Why bother?, it croons. The human desire for a better world is discarded in favor of a cynical arbitrary notion of personal freedom. Instead of learning compassion and shedding her childish selfishness, this Bella learns that compassion is childish and, in a way, selfish.

Now penniless, Wedderburn and Bella make it to Paris. It is reiterated that their predicament is entirely Bella’s fault and that her trying to help the poor was a stupid and selfish endeavor. While Wedderburn sulks on a bench, Bella wanders into a brothel and discovers a satisfactory mode of money-making. Wedderburn disapproves, she breaks into her secret stash of money and sends him home.

What follows is a very long portion of the movie, where Bella is shown sleeping with a lot of freaky men and one woman, as she has an out-of-the-blue relationship with Toinette, the fellow prostitute who has to service a client for free, because he was too ugly for Bella. As the objectification oozes out of the screen, I start to fall asleep … my God, men are boring.

There are some intermissions in the porn, however. Bella starts to go to socialist meetings with Toinette, which are never shown in detail, and we don’t see them discussing any specific ideas, except once where she says that prostitutes “own their own means of production” (fair enough). She also wears a very cute school-girl outfit and seems to visit some medicine-related lectures in a university (?) – not clear. Back to the freaky fucking!

I think this is where she’s supposed to become the “erudite woman” I’ve been reading about in the reviews, but her entire stay in Paris is so incredibly static. She doesn’t learn or improve anything. In the above incident with the ugly man, where she weakly argues in favor of enthusiastic consent, she’s quickly shut down by Swiney (Kathryn Hunter), the madame of the establishment, who calls Bella to her office and shows her an allegedly sick baby. This baby, Swiney claims, is her granddaughter and needs expensive medicine to survive, so the brothel has to run as it does, because if not, the baby would die.

Again, the movie argues for not disturbing the status quo. “This is how the world works”, it says. “If you rebel, babies die!”.

As is already established, Bella doesn’t ask any further questions, and although she’s interested in medicine, doesn’t offer to examine the baby. She just stops talking about consent altogether. What follows are more very boring sex-scenes. It’s not hard to imagine why Lanthimos and McNamara prolonged (my suffering) Bella’s stay at the brothel ad infinitum. At some point, she gets a letter from McCandles informing her that God is sick, and that’s it, she leaves the brothel with nothing learned and goes back to England.

5. Cruelty is Compassion

In her last days at the brothel, Bella ponders cruelty at length. Unlike in the book, she didn’t quite manage to send Wedderburn home; instead, he remains in Paris for some time, following her like a lost drunk puppy, ranting at her and calling her a whore. While lying in bed with Toinette, Bella says that she’s tempted to be cruel to Wedderburn but doesn’t want to succumb to it.

When Bella returns to London and learns about her real providence, this revelation doesn’t elicit a lot of feelings from her. Being upset at that would be too childish, I guess. So, instead, we quickly move on to her trying and failing to marry McCandles. As expected, they’re interrupted by Alfie Blessington, who wants his Vicky back. Bella decides to go with him to learn more about her old life.

At their lavish prison-like mansion, she discovers that she was really unhappy10 and that she was cruel to her staff and enjoyed it. Learning about her selfish past shocks her at first, but we’re quickly reassured that Bella is not Victoria and that she’s defeated the siren song of casual cruelty. She also discovers that her husband wants to sedate her and bring her to a surgeon for a clitorectomy, which she refuses valiantly and shoots him in the foot.

It is fascinating how much the movie concentrates in Bella’s genitalia. The phrase “the thing between your legs” is used frequently throughout the movie to teach Bella about womanhood or something. When Blessington tries to persuade Bella to drink the sedative, with a revolver pointing at her, she looks upon the drink and says that she sometimes wishes to be rid of her searching nature.

So, Bella herself believes that her curiosity, her striving to be and do good, to rid the world of poverty and evil, are a result of her having a lot of sex. This is the thesis of the movie.

Anyway, Bella shoots Blessington and, set on saving his life, brings him to Baxter’s clinic/house to operate on him. She and Max save his life and then (totally non-cruelly and humanely and absolutely humorously and funnily) kill him by swapping his brain with a goat’s.

It's just that some people are deserving of cruelty.

By making Wedderburn as whiny and annoying as possible and Blessington just pure evil, by making Max complacent and Godwin a eunuch, Lanthimos populates his movie with inhuman male characters who seem so thoughtless, lifeless and evil in comparison to Bella that we don’t have another choice than to believe that she’s in the right all the time. In this constellation she’s right to be mean to Wedderburn, she’s right to treat Max like shit, and she’s absolutely correct in her assessment that killing Blessington is the right course of action.

With that Lanthimos just replaces a male oppressor with a female one, without even rattling at existent power structures. That’s not enough, however. With all its nods to the status quo, its derision of Bella’s genuine attempts at helping people, the movie establishes just one way Bella can go: “Conform to the status quo, amass as much status as possible, and then do unto others that’s been done to you.” For it is only Bella who gets to enjoy being on top the food chain, all the other female characters are either treated as sex objects, comic relief or are, unfortunately, Felicity (Margaret Qualley).

Felicity is brought into the world by Baxter and McCandles out of boredom and jealousy at Bella’s grand adventure with Wedderburn. Her birth is shown thusly:

Baxter and McCandles are drunk and very sad. Baxter jokes around that he could make “another one”. Jump cut. A woman is repeatedly getting hit in the face with a ball. Comedy! Turns out, they somehow found another pregnant corpse and did the same thing to her as with Bella. But what’s that? She’s not developing as fast as Bella! A travesty! So, they abuse her, a lot. As her motor skills are developing very slowly and she can’t catch a ball, Max just doesn’t have another choice than to hit her in the face until she falls unconscious. Are you laughing yet?

They continue to abuse Felicity, calling her “it” and “an experiment”, while she continues to not understand what she did wrong. At some point Baxter and McCandles lose interest and give her to Ms. Prim, who treats her equally badly. When Bella returns, she’s shortly upset at Baxter for making “another one”, but she also doesn’t do anything to help Felicity. In the idyllic ending of the movie, we see Felicity finally catching a ball and getting sent to fetch water for Blessington the goat: yay, she’s advanced to a lowly servant. ARE YOU LAUGHING YET?

6. The Incurious Case of Yorgos Lanthimos

With the inclusion of Felicity as a running gag, the film shows a nigh apocalyptic dog-eats-dog world. Baxter would do anything for science, Max would do anything to get Bella, and Bella would do anything for fun and pleasure, anything but show compassion.

In my darkest moments, I put on a tinfoil hat and cannot help but wonder whether these films are praised specifically because they don't reach beyond the existing power structures. Instead, they exist only to uphold a patriarchal system predicated on casual misogyny, exclusion and, most of all, cruelty.

McNamara and Lanthimos cannot fathom a world with no existing oppressive structure. Therefore, there’s is a fundamental flaw in their brand of feminist ideology:

In addition to absolutely and harmfully misunderstanding female sexuality, they also assume that women want to be sexist back, that a woman in power is just a man with a different “thing between the legs”.

But what if women don’t want to perpetuate patriarchal structures? What if they don’t want to take on the traits of the oppressor and just oppress back?

In the epilogue as well as the erratum Gray tells the entire life story of Victoria McCandless M.D., the first woman to graduate from a medical college in Scotland. She was a socialist, a suffragette, lost two of her sons during the Great War and then continued to try and save the world the only way she knew how – medicine and stubbornness. Victoria was an extremely flawed woman and an even more flawed feminist, putting forth ideas which were quite harmful and never backing down from them, putting forth ideas of kindness and love and never backing down from them either – all the while running a clinic for the poorest of the poor and helping women as much as she could.

Although Gray himself couldn’t conceive of a world outside its societal order, he at least tried to conceive of a character who could (writing is tricksy like that). He wrote into existence a woman who didn't just try to change society from within, she tried to abolish its notions of women, sex, love and war altogether, all the while still being part of said society. She failed, she was ridiculed, she died alone, but not forgotten.

At the very end of the movie we’re shown an idyllic scene. Bella reclines on a comfy garden chair, while Blessington the goat dreamily chews on some brush. Ms. Prim and Felicity are playing ball, Toinette is sitting by Bella’s side, just existing, I guess, and Max, the ever-loving husband and utter wet blanket, tells her how awesome she is at medicine. She casts a satisfied glance at her kingdom of cruelty and abuse, smiles and sips some gin.

For all intents and purposes, Bella succeeded, where Victoria failed.

The movie actively and purposefully refutes every progressive, feminist, humanist or socialist notion the book puts forth. Where Gray tries to not sensationalize female sexuality, Lanthimos makes it a spectacle; where Gray writes of Bella’s slow and steady enlightenment, Lanthimos derides this notion, instead insisting on the adherence to a patriarchal status quo. Where the book deals in the ambiguity and ridiculousness of human nature, the movie proffers a cynical black-and-white philosophy and constructs a world where only a chosen few get a seat at the table (or at a comfy garden chair).

But if we, as a society, can’t imagine ourselves trying and failing. If we can’t imagine the complex ambiguity of being a socialist or feminist as an eternal path of learning and compassion, which sometimes leads us to utter stupidity and sometimes to enlightenment. If we can’t do that even in fiction, we’ll succumb to Yorgos Lanthimos’ complacent, cruel, black-and-white all-or-nothing mentality. We’ll mistake cruelty for compassion, basic abuse for feminism, and shower a movie about that with all the awards and accolades, it doesn’t deserve.

Oh … we already did.

↩ 1. The choice is yours, dear reader, to decide whether Archie here has fallen in love with a literal toddler, who cannot comprehend the world around her, or a severely disabled woman, who cannot comprehend the world around her for different reasons.

↩ 2. Granted, the long-winded back and forth is absolutely intentional and is supposed to make you want to skip the chapter entirely.

↩ 3. A socialist organization that exists to this day with) a reputation to boot.

↩ 4. I swear people laughed at that in the movie theater.

↩ 5. At least Barbie had the good sense of decking the man who grabbed her ass.

↩ 6. I don’t want to assume, but someone is sure obsessed with his middle footless leg.

↩ 7. This movie is incredibly straight.

↩ 8. Agency shmagency, amirite??

↩ 9. I guess racist Dr. Hooker was too risqué.

↩ 10. Well, duh! You did commit suicide

Sources:

Gray, Alisdair. Poor Things (Digital Edition). Mariner Books, October 2023

Poor Things. Directed by Yorgos Lanthimos, Element Pictures, TSG Entertainment, Film4 Productions, 2023

Barbie

Hello, Friends!

Barbie has officially made more than one Billion Dollars at the box office and my review, or rather deep-dive, into its plasticky feminist messaging is finally done.

For your reading pleasure, there’s a non-spoiler and spoiler section, in case you’re interested in watching the movie and having some fun first, before diving into its ideology and politics.

So, without further ado. Enjoy!

Welcome to Greta and Mattel’s Play Corner

In a scene near the end of the first act Barbie (Margot Robbie), having wound up in the real world to fix the tear between reality and Barbieland, has been escorted to Mattel headquarters by shady black-clad gentlemen in shady black armored cars. At this point, having suffered a setback of her own, Barbie doesn’t really know what to do next, so she goes along in the hopes that her creators can fix the problem.

She’s escorted to the top floor to meet the management headed by CEO (no name given) played by Will Ferrell. CEO is a kind of evil, but harmless, even dorky creature. He’s aware of the power he holds over little girls’ imaginations (even relishing in it), as well as his responsibility towards the bottom line of the company, and simultaneously he convinces himself that he’s doing it for female empowerment. In other words: he’s a caricature of a corporate shill, blissfully ignoring his male privilege (let’s call him CEO Ken).

As Barbie arrives at the top floor, CEO Ken (along with CFO Ken and COO Ken) convinces her to get back into a giant box (the one in mint condition that Barbies usually come in) to fix the tear in reality. That way, they promise, she can go back to Barbieland and everything’ll go back to normal. She agrees, but before she steps into the box, she has one last request: she wants to meet the female CEO of Mattel, the woman who runs the show.

This seemingly innocent request makes CEO Ken inexplicably angry. Mattel is a company that’s built for and by women, he proclaims. After all, they have “gender neutral bathrooms up the wazoo”, and they did have two (or so) female CEOs, one in the nineties and another one!1 The scene is obviously played for laughs, with CEO Ken being the butt of the joke. But then this phrase explodes out of his middle-aged mouth: “Now, get back in the box, you Jezebel!”, followed by: “What? You’re not allowed to say Jezebel anymore?”

Jezebel? What?

Obviously, Jezebel is supposed to be a jocular stand-in for the word bitch, and I, and others at the theater, definitely chuckled. But (if I may overthink for a moment2) Jezebel is also the woman whose name is synonymous with pure evil, wanton sexual depravity and heresy. The woman who is also undergoing a kind of redemption3 as the victim of biblical misogyny.

Thanks to my obsessive brain, this scene stuck with me longer than most scenes in the movie. The blatant invocation of the worst woman in the Bible, spoken in a moment of misdirected male rage and entitlement, made me wonder. Is this movie supposed to redeem Barbie? Redeem her from all the feminist criticisms hurled her way pretty much since her inception (modeled after a German sex doll no less)? The unrealistic body standards, the consumerist lifestyle, the blonde hyper-sexualized femininity – reexamined and recontextualized in this pink overly stylized movie?

Let’s see.

This marks the end of the somewhat spoiler-free section of the review. In short, yeah, the movie is entertaining and quite funny. The actors are spot-on, and the grand set design alone is worth a watch. I’d definitely recommend watching this movie for the spectacle, the humor, and the warm and fuzzy feeling you get when you don’t have to think about something too hard!

✨ SPOILERS AHEAD ✨ ✨ SPOILERS AHEAD ✨ ✨ SPOILERS AHEAD ✨

✨ Part 1: Pretend Existentialism ✨

The movie begins with a shot-for-shot recreation of the Dawn of Men sequence from Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, wherein Helen Mirren narrates the first arrival of Barbie on the girls’ toy scene, previously dominated by baby dolls and pretend motherhood. While the girls rip off their aprons and ferociously smash their plastic babies into the barren post-war ground, Mirren continues to narrate the evolution of Barbie. If Barbie could be anything4, she says, have a career, her own money and everything she wanted, you could, too. Thus, Barbie solved all the problems posited by the patriarchy and catapulted women into a new and empowered future.

“At least, that’s what the Barbies believe. Who am I to burst their bubble? ”

If anyone could burst my bubble anytime, it’s Helen Mirren

To highlight life in Barbieland, we meet Stereotypical Barbie, as she goes about her perfect day. She wakes up, showers, eats breakfast, and of course changes cute outfits in-between scenes. On her pretend drive through town, she cheerily greets every Barbie she sees. We meet (President) Barbie (Issa Rae), (Lawyer) Barbie5 (Sharon Rooney6), (Writer) Barbie (Alexandra Shipp) during her Nobel Prize ceremony, and so many more Barbies along with their incredible achievements and careers.

Every job of importance, from garbage disposal to the supreme court, is performed by Barbies supporting their sisters with cheers and a heartwarming “Hi, Barbie!” everywhere. Barbieland is a collaborative paradise (albeit within the frame of the real world and its hierarchical structures).

(Main Character) Barbie arrives at the beach greeting even more Barbies, including (Mermaid) Barbie (Dua Lipa), but what’s this? Who’s vying for her attention? Why, it’s (Beach) Ken (Ryan Gosling) and all the other Kens, whose job is … beach, and they’re damn good at it, too. (Beach) Ken tries to impress Barbie by shredding some waves but fails miserably as he collides with the plastic water. Before Dr. Barbie can heal his wounded pride, (Tourist) Ken (Simu Liu), (Beach) Ken’s most bitter rival, tries to taunt him into an epic beach-off, but is stopped by Barbie.

Anyway, how about a huge blow-out party with all the Barbies and a choreography to bespoke music? Barbie’s got you. As the Barbies dance and the Kens try to get their attention, we know that it’s the best night ever, we all wanted this night, indeed every night, to be just like this – forever. By the way, have you ever thought about dying?

This one question not only derails the party but is also a harbinger of terrible change in (Main Character) Barbie’s life. As early as next day she starts “malfunctioning”. Her heels fall flat on the ground, the pretend water in her pretend shower is cold, and she falls off of her roof instead of gracefully gliding into her car as usual. After a good 30 seconds of barfing noises at the sight of her flat feet7, the Barbies tell Barbie to go to Weird Barbie (Kate McKinnon), a Barbie that has been played with too hard, has mangled hair and is always in the splits.

At Weird Barbie’s weird house, Barbie asks Weird Barbie to fix her so that she can go back to her perfect life. Unfortunately, it’s too late. The girl who’s been playing with her is sad, and her emotions somehow opened a rift between the real world and Barbieland and are now affecting (Stereotypical) Barbie’s emotional state as well. After some hesitation, Barbie agrees to go to the real world, after the actual threat is revealed – whole body cellulite!8

(It is, indeed, later revealed that the horrible things which made Barbie malfunction are perpetual thoughts of death and a life with whole-body cellulite9.)

Barbie goes to the real world accompanied by Ken, who was taunted by Ken to go with her. After arriving at Venice Beach, they both feel a clear shift in perception. While Barbie feels the unwanted attention from men with definite violent undercurrents, including sleazy comments, Ken is delighted by all the free and positive attention as well as the basic respect people seem to have for him. After some hijinks, Barbie sends Ken away so that she can think and figure out where she can find the girl she came to console.

She closes her eyes, breathes deeply and reaches out. Her mind is flooded with memories of a mother-daughter relationship that seems to have gone sour as soon as the kid hit puberty. With the help of the memories Barbie is able to find out where the girl goes to school. When she opens her eyes, however, everything feels different. She looks around and sees beauty – in small interactions, in a family going for a stroll, and in an old woman sitting next to her on the bench (Ann Roth10). Barbie looks at the woman, and at the height of her first burst of human emotions she accepts ageing and death, as she tells the woman how beautiful she is, to which she replies, “Don’t I know it!”. Beautiful scene, movie over, let’s go cry in the bathroom!

Unfortunately, Ken comes back with incredible news of his own: the real world is run by men with the help of a thing called patriarchy, which is great and has horses and stuff. Barbie doesn’t get to hear the great news11, however, as they have to depart to the school she saw in her vision.

Which brings us to the Jezebel scene. Barbie has just been shut down by Sasha (Ariana Greenblatt), who blatantly told her that Barbie has not saved womankind from anything and has even added to their plight by propagating unrealistic body standards, a wildly consumerist lifestyle, a very narrow white thin definition of femininity, and basically called her a bimbo (haven’t we been reclaiming this word for the last decade?). By the way, these concerns remain largely unexamined within the movie, except for when they’re uttered by a precocious teen, which dismisses them outright.

However, credit where credit is due: the criticism of Barbie being less of an idea and more of a product is lightly touched upon in a very visually satisfying way. The production design of the Mattel headquarters has the same plasticky artificiality as Barbieland and shows a world where a bunch of man-children pretend-play with big ideas and money in phallically shaped buildings without any notion of the real world they’re influencing12. Unfortunately, this very vanilla criticism doesn’t go beyond showing the upper management of Mattel as a bunch of adorkable corporate Kens.

They couldn’t hurt a fly

In a very funny Benny Hill-inspired chase sequence, Barbie escapes the Corporate Kens and gets scooped up by Gloria (America Ferrera), the CEO’s executive assistant, Sasha’s mom and (gasp) the “girl”13 who was actually playing with (Main Character) Barbie. Bored in her job, sad because she’s losing touch with her daughter and overall unsatisfied of what she’s become, Gloria started dreaming of a simpler time – a time when play was equally as important as work and other responsibilities. Unfortunately, her real-world troubles crept into her blissful playing time, and so (Perpetual Thoughts of Death and Full-Body Cellulite) Barbie as well as the rift between the two worlds was created.

As soon as Gloria and Barbie reunite, Barbie knows what to do. She needs to take Sasha and Gloria to Barbieland to show them how a society run by women actually works. After all, this is what Barbie was supposed to do in the first place, right?

✨✨ History Excurse ✨✨

Barbie was first marketed as a teen model – a young woman about town, who had a ton of different outfits, her own money and no dependents. From her inception, she herself wasn’t dependent on outside male validation and was neither forced to nurture male egos nor any children. Which means that her relationships with her siblings, friends and cousins, as well as Ken, were based on actual sympathy rather than restrictive norms. In short, yes, Barbie was a relief from the constraining gender roles of the 1950s.

However, Women were on the cusp of liberation in the 1960s anyway, Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique came out in 1963, sparking second-wave feminism (and everything good and bad that came with it). Ruth Handler, co-founder and president of Mattel, who is credited with inventing Barbie, saw that women were changing in the post-war years and understood this political climate far better than her husband or any man could. She knew that Barbie would sell, not because she would inspire young minds, but because she actually looked at young girls as a viable demographic to sell to14.

However, Women were on the cusp of liberation in the 1960s anyway, Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique came out in 1963, sparking second-wave feminism (and everything good and bad that came with it). Ruth Handler, co-founder and president of Mattel, who is credited with inventing Barbie, saw that women were changing in the post-war years and understood this political climate far better than her husband or any man could. She knew that Barbie would sell, not because she would inspire young minds, but because she actually looked at young girls as a viable demographic to sell to[14].

✨✨✨✨✨✨✨✨✨

Instead of acknowledging the fact that Barbie is a consumerist product that sometimes manages to inspires people, and how dangerously intertwined capitalism and culture actually are, the movie staunchly (stubbornly even) positions itself in favor of Barbie always having been an Idea (capital letter “I”) for the greater good15. Even though Ruth Handler appears twice in the movie as an adorable old lady ghost played by Rhea Perlman (an adorable old lady), both appearances paint her as a benevolent God, helping her creation to finally find herself, and less as a person with financial as well as creative ambitions. In the grand scheme of things, she’s also just a figment of imagination in this particular installment of Greta’s play corner. She is: (Simplified Beyond Recognition Ghost of Ruth Handler) Barbie16.

Adorable

✨ Part 2: Pretend Patriarchy ✨

Barbie, Gloria and Sasha make it back to Barbieland, followed by the (Upper Management) Kens, only to discover that Ken has returned there earlier (Biff style) and has instituted his own version of patriarchy with what he’s learned from the real world (brewskis, horses and submissive women Barbies).

Introducing: (Stealing a Time Machine, Going Back to the Past and Giving the Almanac to Your Younger Self, so that He Can Get Rich and Become Donald Trump) Ken. Accessories include: Sports Almanac, Time Machine, A Cane to Abuse People With and an Attitude. Out Now! Only Free.99

In his newly formed Kendom (Biff) Ken has brainwashed all the previously amazing Barbies into serving him and the other Kens, while being their “long-term long-distance low-commitment casual girlfriends”. He’s also destroyed Barbie’s dream house and turned it into his Mojo Dojo Casa House, which is awesome and has a mini fridge for his brewskis.

The patriarchy Ken propagates is, of course, played for laughs most of the time, as the Kens frolic about Kendom kensplaining movies, cars, sports and money to unsuspecting Barbies. However, again, the movie is actually quite close to making a point.

The Kens feel disenfranchised and trapped both in their dependence on the Barbies’ attention and their absolute lack of actual contribution to the world they’re living in. This results in a Barbieland version of arrested emotional development and a lack of a distinct sense of self. So, they sink ever further into a morass of loneliness, petty rivalries with other Kens and emotional immaturity, which results in them not being able to form any viable emotional connections. Instead of dealing with these emotions, they blame the Barbies for their misfortune and, as a result, subjugate them, vandalize their property and take over Barbieland by force.

These are the effects of the patriarchy on men. Greta identifies and shows them with terrifying clarity. How awesome is it then that she’s created a framework, a world fully built on play and fanciful thoughts, to playfully show us how these effects could be ameliorated – not a solution, but a suggestion of how, for example, women and men could collaborate to get out of this mess together; or how the Kens can bond in a meaningful way to understand that they need each other and not some fake subjugated girlfriend to form a strong sense of self; or anything really…..

✨ Part 3: White Feminism and The Speech ✨

After seeing what Ken has done to Barbieland, Barbie falls (literally) into a deep crisis and sends Gloria and Sasha away. Later she's scooped up by (Weird) Barbie and some allies, who didn’t fall for Ken’s version of patriarchy. Sasha, however, can’t leave Barbieland in disarray, and together with discontinued doll Alan (Michael Cerra), who is one of a kind and therefore even more lonely than the average Ken, they return to (Weird) Barbie’s house, where all of the misfits have gathered.

Gloria asks Barbie what’s wrong, and Barbie (by now almost human) breaks down, lamenting that she’s neither pretty, nor smart, nor interesting enough (the narrator chimes in again at this point, to lampshade Margot Robbie’s beauty).

As heartbreaking as it may seem to see Margot Robbie say that she’s not beautiful enough, Barbie’s statement doesn’t make sense. For whom is she not beautiful/smart/interesting enough? Barbieland appreciates her as she is, Kendom is a joke and no one cares about the Kens anyway, and she’s not human yet, so the real world is also not a concern.

This is not an existential crisis; it’s a prompt for The Speech.

After hearing the absolutely beautiful and perfect in every way Barbie utter those words, Gloria turns into (Gloria Steinem) Barbie and delivers the emotional climax of the movie (America Ferrera is a great actress and she does great in this scene, no shade)17.

After hearing the absolutely beautiful and perfect in every way Barbie utter those words, Gloria turns into (Gloria Steinem) Barbie and delivers the emotional climax of the movie (America Ferrera is a great actress and she does great in this scene, no shade)[17].

“It is literally impossible to be a woman. You are so beautiful, and so smart, and it kills me that you don’t think you’re good enough. Like, we have to always be extraordinary, but somehow, we’re always doing it wrong.

You have to be thin, but not too thin. And you can never say you want to be thin. You have to say you want to be healthy, but also you have to be thin. You have to have money, but you can’t ask for money because that’s crass. You have to be a boss, but you can’t be mean. You have to lead, but you can’t squash other people’s ideas. You’re supposed to love being a mother, but don’t talk about your kids all the damn time. You have to be a career woman, but also always be looking out for other people. You have to answer for men’s bad behavior, which is insane, but if you point that out, you’re accused of complaining.

You’re supposed to stay pretty for men, but not so pretty that you tempt them too much or that you threaten other women because you’re supposed to be a part of the sisterhood. But always stand out and always be grateful. But never forget that the system is rigged. So, find a way to acknowledge that but also always be grateful. You have to never get old, never be rude, never show off, never be selfish, never fall down, never fail, never show fear, never get out of line. It’s too hard! It’s too contradictory and nobody gives you a medal or says thank you! And it turns out in fact that not only are you doing everything wrong, but also everything is your fault.

I’m just so tired of watching myself and every single other woman tie herself into knots so that people will like us. And if all of that is also true for a doll just representing women, then I don’t even know.”

We have to talk about this.

Gloria’s speech is the emotional core of the movie, it is well delivered and just feels right. The impossible standards, the contradictory requirements, just the pure insanity of being a woman – finally someone said it. Finally, you, Gloria, set the record straight:

“By giving voice to the cognitive dissonance of being a woman under the patriarchy, you robbed it of its power. ”

But, really?

What about the systemic oppression of marginalized women, the everyday threat of sexual violence, the systemic attack on women’s bodily autonomy? What about the fact that men hold most positions of power, regardless of how good it feels to ✨slay✨? What about the pay gap, unpaid care work, emotional labor, the frickin’ thigh gap …. the orgasm gap, for Christ’s sake!

What about the actual patriarchy?

Although we see a variety of races, body types and gender identities in Barbieland, their experiences with the aforementioned patriarchy are not mentioned or highlighted in any kind (if they have any lines of dialogue at all). Our main character, however, is (Stereotypical) Barbie, with the stereotype being: white, cis, thin and able. By giving this particular main character most of the screen time and dialogue lines, Gerwig opts for a simplified non-intersectional approach, saying that all women are the same and face the same diffuse oppression. Her kind of patriarchal oppression is highly individual, more of a set of contradictory guidelines than an actual threat.

In short – the movie is about how patriarchy makes one feel, not what it actually does.

Having white privilege doesn’t mean that Barbie’s life is without hardship, as we see in the short time she spends in the real world. As soon as she arrives, she is immediately sexually harassed and intimidated18. She has uncomfortable gender roles and expectations hoisted upon her and should she choose to become human, she’ll experience a barrage of double standards.

However, her and Ken’s white privilege comes in handy, after a man at the beach sexually assaults Barbie and she instinctively punches him in the face. She (and Ken) get arrested presumably for assault and immediately let go, but not before Barbie is verbally and very openly harassed by the cops processing them. Following that, they decide to get some less revealing clothes and get arrested again, this time for stealing. But again, they’re immediately let go, despite not having any money or lawyers. Both incidences of criminal behaviour result from men harassing Barbie, and although it’s an uncomfortable situation, nothing else of consequence happens to her (or Ken).

It’s both hard and very easy to imagine what would’ve happened if (Writer) Barbie or (President) Barbie had chosen to go the real world instead. Their experiences would’ve vastly differed from what (Stereotypical) Barbie encountered, as Black women are much more likely19 to be sexually assaulted and criminalized.

Another great example of Barbie’s (and Ken’s) easy accessibility in the world comes soon after, when she goes to Sasha’s school in this outfit:

She proceeds to wander about the school (Ken even goes into the library), until she finds Sasha and her friends in the cafeteria. Having acquired her target, Barbie approaches them, while no-one bats an eye at a weirdly happy lady in a weird outfit, and talks to them proclaiming that she’s Barbie.

Again, it’s not hard to imagine what could’ve happened, if (Doctor) Barbie, played by trans actress Hari Nef, had been in Barbie’s stead. As the current inhuman campaign against trans individuals seeks to take away20 their human rights as we speak, with trans women in particular being called groomers and rapists21, this scene would’ve played a lot more differently and (I imagine) violently.

White (cis, thin, etc.) privilege is baked into the very fabric of the movie - the choices Barbie (and Ken) are allowed to make and the places they’re allowed to visit without repercussions are proof of that. As soon as a woman diverges from the “norm”, however, patriarchy and the subsequent oppression become even more of a threat to physical and mental health, additionally to the “cognitive dissonance of being a woman under patriarchy”.

Actually, we only have to look as far as Mattel’s own back yard for further examples of this terrible dichotomy: In 2020 a report22 from China Labor Watch, Action Aid France and Solidar Suisse came out and revealed the horrific conditions the female workers who make Barbie in Mattel factories have to face, including rampant sexual harassment. Although Mattel has been alerted to these issues several times, they chose not to act on them.

Mattel is not interested in making a movie about how the practices of patriarchal structures actually affect women. A truly feminist film would be incredibly bad for business, you see. What they’re interested in is a veneer of feminism and wokeness, which they’ve easily achieved just by hiring indie-darling Greta Gerwig.

Patriarchy is not the same for everyone, oppression is not some diffuse concept and, unfortunately, you cannot rob either of their power just by stating how it makes one particular group of women feel.

✨ Conclusion: I’m a Barbie Girl, in a Barbie World? ✨

After the speech, (Writer) Barbie, whom the others abducted to try to deprogram her (questionable), snaps back to reality, because of the aforementioned “giving voice to the cognitive dissonance……..” (bla bla). And so, the (Guerilla) Barbies formulate a heist plan, which they narrate while standing over a map of Barbieland (let’s get heisty!).

They distract the Kens with the already deprogrammed Barbies by making them kensplain stuff, while forcing the brain-washed Barbies into a pink van23, subjecting them to snippets of dissonant double standards for women until they get woke. It doesn’t take long, as there are like seven Barbies in total. The crown jewel of their plan is then to play the Kens against each other by showing affection to their rivals.

“Now that they think they have power over you, they’ll start wondering whether they have enough power over each other.”

It works, of course, and culminates in a grand epic awesome beach-off between the warring factions of Kens led by (Beach) Ken and (Tourist) Ken respectively. It’s also a musical number, with a dance and everything. It’s amazing!

In his song, (Beach) Ken laments his fate of being Just Ken. Is it his “fate to live and die a life of blonde fragility”, he croons? What would it take for her to “see the man behind the tan” and fight for him? In the course of the musical number, however, Ken becomes increasingly aware of his predicament, and the song pivots into a grand dance number, with all the Kens realizing that they’re actually “enough and they’re great at doing stuff”, and ends with them holding hands – emotional connection achieved, feel the kenergy!

“My name’s Ken and so am I, put that manly hand in mine. So, hey world, check me out, yeah, I’m just Ken!”

Meanwhile, the Barbies storm the capitol and reinstate the Barbieland constitution, thus ending Kendom and saving themselves from patriarchy and taking back their dream houses.

And if this was the end of the patriarchy story line, I would’ve been incredibly happy (mostly because the song made me inexplicably happy to begin with).

The Kens did the work and, mirroring the Barbies’ examination of their congnitive dissonance under the patriarchy, rejected the pure performance of masculinity in favor of their need for genuine emotional connection and self-actualization – awesome!

Now, they can go to the Barbies, apologize and rebuild Barbieland as a land of equal opportunity for everyone (except Barbies with cellulite or flat feet ✨barf✨).

Upon their return from battle and their super awesome song, however, Ken doesn’t take the destruction of his kingdom and Mojo Dojo Casa House very well, and, although the song should’ve done the heavy lifting, Barbie has to apologize to him for having boundaries24.

After she does all the emotional labor for Ken and reiterates that he has to find a sense of self outside of Beach and Barbie, the (Corporate) Kens finally catch up with the plot and are ready to close the rift and return everything to its former glory. (President) Barbie, however, doesn’t want to return everything to how it was, instead giving the Kens their first seats as minor judges.

“In a couple of years, the Kens will have the same amount power in Barbieland as women have in the real world.”

Why? Why does Barbieland has to function like the real world? Why can’t we use the opportunity and at least try to find a solution to the obvious problems that plague the us?

Well, that’s obviously not why the Barbie movie was made.

Much like Barbie herself, it’s a pink, beautiful and smart summer blockbuster and just like Ruth Handler, Mattel and Greta Gerwig have found a lucrative demographic to cater it to – us. The perpetually online, the hyper aware, the helpless in the face of a burning world.

They identified that they can regurgitate to us the same consumption friendly “girl power feminism” from any Barbie commercial since the 80-ies, but with a sprinkle of commodified feminist language. It’s no coincidence or surprise that everyone, who saw this movie already has the readily available internet socio- and psycho babble vocabulary to talk about it.

In the end, by holding on to the existing patriarchal structures of the real world, the concept of the “flattering top”25, cellulite jokes or by not giving enough dialogue to any of the diverse cast, the Barbie movie doesn’t move anything, doesn’t go beyond what we already know.

It’s just a consumerist product made for our generation.

Stare into the void

Meanwhile, Barbie is ready to become human. The ghost of Ruth Handler appears and takes her to the void, where she makes sure that Barbie understands what life and death actually mean. She takes Barbie’s hands and shows her what humanity is about (take notes, there’ll be an exam): A Billy Eilish song starts playing and Barbie closes her eyes. She sees memories shot on the crappiest camera you can find. Women laughing, children giggling, adorable old ladies smiling, laughing, giggling, smiling, laughing, giggling…..

She opens her eyes, a tear rolls down her perfectly symmetrical face, she smiles.

So, what is an icon to do when she finally becomes human? How can she make meaning, instead of being an object of imagination? What does it mean for her to be a woman?

Do we meet her at a university educating herself? Do we get a glimpse of her being a community leader? Do we see her volunteering at a women’s shelter?

No, silly. She’s a woman now. We meet her at a gynecologist appointment, of course.

↩ 1. If you’re interested: Jill Barad was CEO from 1997-2000 and Margo Geordianis from 2018-2020

↩ 2. Sike! I don’t need permission for that!

↩ 3. Michael Satchell (Jan. 25, 2008). Jezebel was a Killer and Prostitute, but She had Her Good Side: The reigning icon of womanly evil. U.S. News and World Report (last accessed: Aug. 08, 2023)

↩ 4. “You Can Be Anything” is a trademarked statement held by Mattel since 1984. In 2015 it became the official Barbie slogan. (Natalie Yeung (Jul.21, 2023). The Barbie “You can Be Anything” Slogan. Profolus (last accessed: Aug. 3, 2023))

↩ 5. Curvy Barbie was added to the Barbie line-up in 2016 among other body-shapes like “petite” and “tall”

↩ 6. Kudos on the incredible casting choice!

↩ 7. Huh, for a society that has embraced disabled Barbie, they sure are not kind to disabilities that they deem gross or unusual

↩ 8. Huh, for a society that has embraced Fat Barbie, they sure are quick to jump on the fear-mongering wagon of cellulite, a thing that has been specifically invented by men to make women hate their bodies and spend an inordinate amount of time and money fixing it.

↩ 9. Kelsey Miller (May 14, 2018). Cellulite Isn’t Real. This Is How It Was Invented. Refinery29 (last accessed: Aug. 3, 2023)

↩ 10. Oscar-winning costume designer and overall bad-ass

↩ 11. Because she doesn’t prioritize his thoughts and feelings (sic!)

↩ 12. That’s some Succession level commentary right here.

↩ 13. (This video has nothing to do with my review, I just really like it.) Rowan Ellis (Aug. 1, 2023). the perpetual infantilisation of millenial women. Rowas Ellis - YouTube Channel (last accessed: Aug. 03, 2023)

↩ 14. After all, Mattel was the first ever toy company to broadcast commercials directly to children through their ties to the Walt Disney’s Mickey Mouse Club.

↩ 15. Look, honey! Greta’s playing revisionist history. How cute!

↩ 16. BTW, I’d love an older Barbie edition! I’d kill for feminist icon Jane Fonda Barbie, laid back Lily Tomlin Barbie … ANGELA LANSBURY BARBIE!!!!

↩ 17. Buckle up, it’s a long one!

↩ 18. Victims of Sexual Violence: Statistics. Rainn (last accessed: Aug. 03, 2023)

↩ 19. National Black Women’s Justice Institute (Orginal Post: Apr. 2021, Updated: Apr. 11, 2021). Black Women, Sexual Assault and Criminalization. (last accessed: Aug. 04, 2023)

↩ 20. hrc.org Resources (Last updated: Jul. 25, 2023). Map: Attacks on Gender Affirming Care by State. Human Rights Campaign Foundation (last accessed: Aug. 03, 2023)

↩ 21. Henry Berg-Brousseau (Aug. 10, 2022). NEW REPORT: Anti-LGBTQ+ Grooming Narrative Surged More Than 400% on Social Media Following Florida's "Don't Say Gay or Trans" Law As Social Platforms Enabled Extremist Politicians and their Allies to Peddle Inflamatory, Discriminatory Rhetoric. Human Rights Campaign Foundation (last accessed: Aug. 05, 2023)

↩ 22. ActionAid France, China Labor Watch, Solidar Suisse (Dec 05, 2020). China: NFO report reveals Barbie-making female workers in Mattel Group’s factories are exposed to risks of sexual harassment. Business & Human Rights Resource Center (last accessed: Aug. 04, 2023)

↩ 23. Is this a reference to A Clockwork Orange?

↩ 24. You know who doesn’t apologize for brainwashing her friends, destroying her house and trying to take over the country?

↩ 25. Gray Chapman (Nov. 28, 2016). What Do We Really Mean When We Say Something Is “Flattering”?: Often, the word “flattering” simply boils down to camouflaging your body’s flaws. Racked (last accessed: Aug. 03, 2023)

Asteroid City

Hi, guys!

I’m slowly chippping away on my summer reviews, starting with this deep-dive into Wes Anderson’s newest pastel-colored masterpiece Asteroid City.

I genuinely think that this movie is Anderson at his best, perfectly balancing his highly stylized visual style with a deep emotional core.

The Jawbreaker with a Squishy Center

Directed by Wes Anderson

What is a director like Wes Anderson to do when it’s time for him to make his own version of The Fabelmans? A deeply personal drama, about the interconnectedness of family, love and grief. We’re all not getting any younger, so how do we reflect on our lives when the time comes? How do we gaze into the abyss of our past choices?