Asteroid City

The Jawbreaker with a Squishy Center

Directed by Wes Anderson

What is a director like Wes Anderson to do when it’s time for him to make his own version of The Fabelmans? A deeply personal drama, about the interconnectedness of family, love and grief. We’re all not getting any younger, so how do we reflect on our lives when the time comes? How do we gaze into the abyss of our past choices?

Wes Anderson thinking with his eyes

Well. In case of Anderson, we direct the outstanding thespians of our newest movie to act as mime-like and detached as possible, throw in an alien for good measure, and most importantly, hide the touchy-feely stuff in the middle, where it’s compressed by layer upon layer of pastel sugary candy. Also, the roadrunner – meep meep!

We open on a scene in black-and-white Academy ratio, as we’re greeted by Bryan Cranston in his best 1950s attire, narrating a special televised production as well as the behind-the-scenes of Asteroid City, the newest play by famous all-american playwright Conrad Earp (Edward Norton). Earp has recently finished his magnum opus about infinity and whatever else and is ready to put it on stage for our entertainment. The director Schubert Green (Adrian Brody) and the actors are introduced, and then we’re quickly moved to the actual play.

Intense

In the most pastel widescreen you’ll ever experience (at least until the next Anderson movie), the play within a narrated televised production opens with a train happily transporting Californian goods (so many avocados) across the desert, set to an Alexandre Desplat soundtrack.

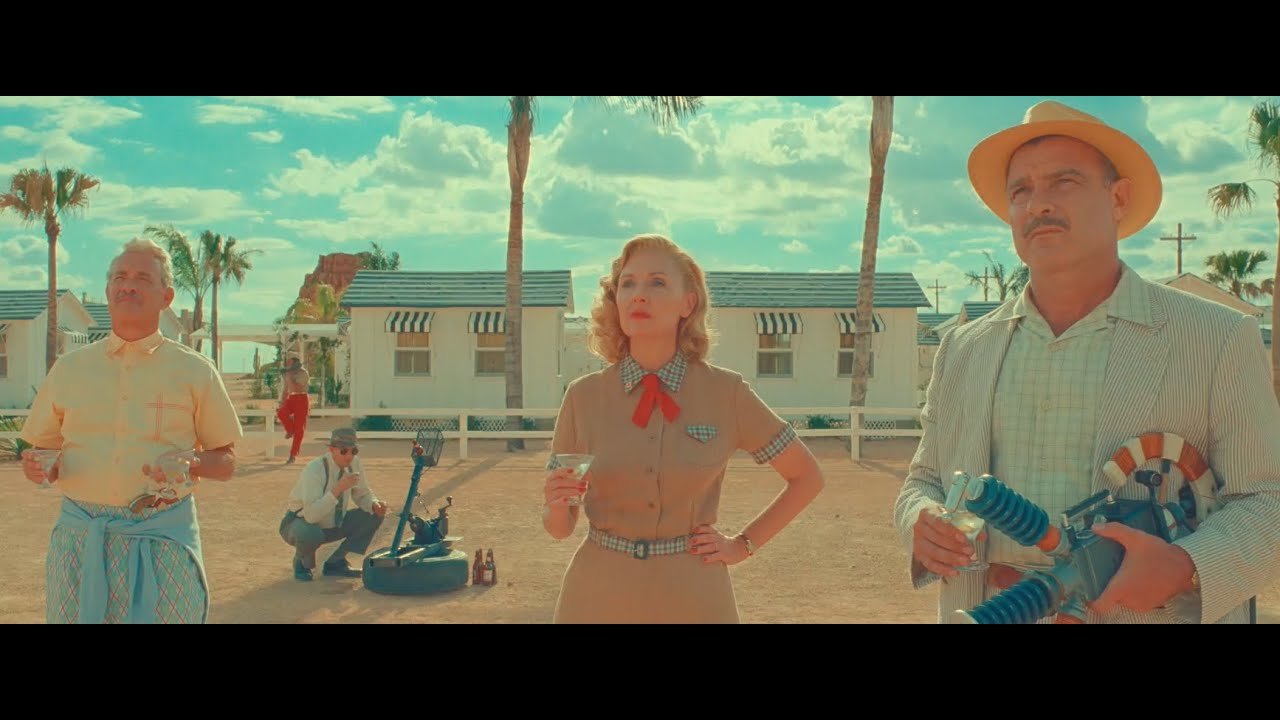

The train passes a desert town named Asteroid City that consists of a garage and motel, as well as an observatory and research station at the huge and by all accounts ancient asteroid crater (open for visitors from 9 to 5, Sundays closed). Asteroid City is also mostly empty allotments that can be bought in a vending machine at the motel (retro future is here).

Everything you need, while grieving your dead wife in the middle of nowhere

As the train goes on its merry way, transporting its goods to avocado toast lovers everywhere, a broken down car is being towed into the garage. Here, we meet (some of) our protagonists: Augie Steenbeck (John Hall/Jason Schwartzman), war photographer and recent widower, Woodrow Steenbeck alias Brainiac (Understudy/Jake Ryan), his son, a genius and one of the winners of the Junior Stargazer and Space Cadet Convention, which takes place in Asteroid City, and Augie’s three young daughters Andromeda, Pandora and Cassiopeia (Ella Faris, Gracie Faris, Willan Faris).

Augie phones his father-in-law Stanley Zak (Tom Hanks), with whom he has a contentious relationship (we know that, because one of them is a WASP). Stanley chews him out for not yet telling the children that their mother died three weeks ago, but also begrudgingly agrees to come to Asteroid City to get the girls, while Augie stays with Woodrow for the convention, at which he is an awardee for inventing a… scientific thingamajig (yes, I’m spoiling everything, except the inventions of the junior stargazers – don’t at me).

Like many a small child, Andromeda, Pandora and Cassiopeia, much like their namesakes, move in mysterious, barely comprehensible ways and contain multitudes. Dressed in frilly clothes, they vehemently deny being princesses, instead choosing to be either vampires, mummies, witches or whatever strikes their fancy in that particular moment. However, as Augie finally confesses to his children that their mother is dead and that he’s been keeping this from them (mostly, because he doesn’t want to confront his feelings, let alone the feeling of his children), the girls are the only ones who, despite their very limited comprehension of death, start working though their grief, albeit in a very peculiar way.

When Stanley arrives, the girls are hard at work, having stolen their mother’s ashes and performing a resurrection ritual, while burying the ashes in a hole behind the hotel. Naturally, he scoffs at the inappropriate burial place and wants to bury the ashes in a proper place, although, after much witchy protest he agrees to leave the ashes in the hole until after the convention.

While the little starlets mill about the desert town, the other participants of the convention arrive in Asteroid City. The awardees with their parents, the military led by General Gibson (Jeffrey Wright) which funds the whole convention and gives out the awards as well as a grant to promising young scientists, a stranded group of cowboy musicians (who are just…there), and a primary school group with their young teacher. It’s kind of a summer camp … with emotional baggage and aliens.

While his sisters move throughout the movie largely undisturbed and uncontested, from the get-go Woodrow has a much more limited scope of movement. He’s trapped in a tight observational corset of everyone around him. His peers, when after the awards ceremony they practically force him to sit with them, so that he doesn’t have time or space to start processing the death of his mother; his father, who takes the knowledge that Woodrow already suspected that she was dead as a sign that everything’s alright; and lastly his own desire to squash his grief with the sheer power of his youthful arrogance and enormous brain. So, as the awardees retire for the night and Woodrow awkwardly tells his love interest Dinah (Grace Edwards) that his mother has died, he tries his best to be nonchalant about it (it doesn’t work).

Augie, meanwhile, has found his own way of salvation (or at least distraction) in Midge Campbell (Mercedes Ford/Scarlett Johansson), a movie actress (heh, an actress playing and actress playing an actress – neat!) and Dinah’s mother. With their motel windows being opposite each other, they start talking and bonding over their profound loneliness and trauma – Augie from losing his wife and being an absentee father, and Midge from being used and abused by men her entire life and being an absentee mother (fun all around). In typical Anderson fashion, the characters are framed opposite each other, confined in stylized sets that reflect their character, while rarely actually sharing a scene together, emphasizing their loneliness on a visual level. Together they rehearse the depressive dialogue from Midge’s upcoming movie, where Augie plays the part of the husband, left behind after his wife commits suicide (it’s not subtle). They also sleep together.

Craters everywhere – their souls are as pockmarked as the surface of the moon.

An alien decides to crash the party midway through the movie and steal the eponymous asteroid. Augie takes a picture.

The universe is chaos, relinquish control – give in.

Say cheese!

Unfortunately, because we’re (oh so) human and need a reason for everything, the second half of the play takes place in military-imposed quarantine, as the government tries to hush up what’s happened in Asteroid City, while subjecting the characters to physical and psychlogical tests. Just like Augie tried to hide the fact that his wife has died to avoid confronting his feelings of inadequacy and helplessness, General Gibson does the same thing, deferring to protocols and a memo from the president for guidance.

However there’s no quarantine on the truth, and inside Asteroid City the minds wander. The young geniuses, in an act of light treason, steal some equipment from the observatory and try to, unsuccessfully, contact the alien, while their parents are driven to a murderous rage by boredom and the excellent Martinis from the Martini vending machine at the hotel.

Eventually the truth gets out thanks to an intrepid school reporter and Augie’s picture and Asteroid City turns into a spectacle and favorite destination of every believer out there. As General Gibson is about to announce the end of the quarantine, the alien makes a second appearance to return the asteroid, the general tries to reinstate the quarantine immediately after the last visit, but the characters revolt, using the awardee’s inventions to shoot their way out of the camp.

Behind the scenes of Asteroid City life also rife with trauma and loss. The director Schubert Green is going through a painful divorce and living backstage during the production. While the writer Conrad Earp, who is implied to have been in a romantic relationship with John Hall, has tragically died before the televised production and left a crater of his own.

After the second appearance of the alien, Hall exits the set in an existential crisis and presumably grieving his romantic partner. He states that he still doesn’t understand the play, he doesn’t know what the alien or any of it means and goes to Schubert for guidance. The director tells him that he doesn’t have to understand the story to tell it.

Confused, Hall goes out for a smoke and by stroke of fate meets the actress, who was supposed to play his wife (Margot Robbie), but was cut out of the production. Together, standing on opposite balconies, mirroring the scenes Augie shares with Midge, they recite the monologue they were supposed to have near the end of the play. A dream sequence, where Augie meets his late wife on the moon and they just talk – no goodbyes, no saintly advise, just one more precious moment with a loved one.

Watching a Wes Anderson movie is always a study in symbolism. Like an old-timey explorer (hat and all), you descend into a flurry of stylized images, perfectly symmetrical shots and quirky acting. Underneath the sometimes impenetrable set dressing, however, is always an emotional core – flawed patriarchs, broken (man)children suffering from the consequences of arrested development, family life mirroring class struggles and vice versa. And at first glance, Asteroid City is no exception.

Augie, Stanley, Schubert, Conrad might be considered patriarchs – flawed, arrogant, self-absorbed. Woodrow and the other junior stargazers are typical precocious children acting like adults, and their parents are detached vultures profiting from their children’s genius ideas (as is the military).

What makes Asteroid City unique, however, is that the characters that would’ve been prominent or even main characters in other Anderson movies are set dressing, red herrings, deployed to conceal a surprisingly deep exploration of male grief and, how men in particular are allowed or not allowed to show emotions. As an alternative to open grief Anderson deliberately offers the protagonists escapism in the form of the exploration of the stars, endless talking about anything else than the actual topic at hand and juvenile (“boy”) interests like jetpacks, lasers, soldiers, cowboys and aliens. If we look closer, however, the soldiers are tired and helpless, the cowboys are total softies and artists at heart, and the alien is just kind of there, indecipherable in its purpose. Every character in the movie, including the writer, director and actors, revolves around a huge crater in the middle of the Nevada desert – at some point looking at it becomes inevitable.

When the quarantine is lifted and the world has lost interest in the existence of aliens, Augie wakes up to find everyone but his family gone, including Midge. Before breakfast, despite Stanley’s protests, which the sisters win simply by exhausting him, the Steenbecks decide to leave the ashes in the hole behind the motel, choosing to leave her at the crater – a wound that never really closes.

Or, uhhhh … does close … sometimes

Augie admits that he was going to abandon his children with their grandfather, but has since changed his mind, while Stanley finally admits that he never liked Augie, but that they’re welcome to stay as long as they like, choosing family over personal dislikes. Only then, after freeing themselves of their own and the world’s expectations, are they allowed to leave. They all sit down in the Asteroid City diner before departure, and Augie gets a note from Midge with her P.O. box address on it, while Woodrow has hooked up with Dinah the night before and has been awarded a $5000 grant, indicating that they’re both ready to move on (or at least try).

“Clear vision ahead with a rear vision mirror” (subtle)

They were the first to arrive and the last to go, it is their denial we’ve been experiencing, their coming to terms with an immeasurable loss – it is them we want to give a hug, pat them on the head and say “there, there”.

But, for the purposes of not being too dramatic and entirely discarding escapism as a valid coping mechanism for grief, the movie closes with the roadrunner dancing (yes) to Alexandre Desplat, while credits roll.

Meep away!

The miniatures are also awesome!